Utagawa Hiroshige was a master of Japanese woodblock printing. He had an observational, unbiased eye and captured important landscapes in Japanese history. More notably, he captured the View of Takanawa in Moonlight during the newly lifted restrictions on Japanese trade with the western world. He paints a serene scene that shows a peace that was two hundred years in the making.

Hiroshige was a master of ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) art and tradition. Also known as Ando Hiroshige, he wasn’t always known as an artist. He was raised in Edo or modern-day Tokyo. He had a heavy samurai background, which wasn’t uncommon because the Tokugawa Shogunate took control of Japan. Hiroshige’s parents passed when he was very young – about twelve years old. He belonged to a fire warden family that monitored the Edo Castle. Once his father passed, young Hiroshige took over as the fire warden. He took the job very seriously, but it came with a lot of down-time. There weren’t many fires at the Edo Castle that needed to be extinguished. In his solitude, he began to dabble in painting.

Hiroshige fell in love with painting and sought out for a formal education in it. Though he was still working as a fire warden, he also took on an apprenticeship where he’d work on illustrations for books and single-sheet ukiyo-e prints. The subject matter for these books and prints tended to be of female beauties in the red-light district and kabuki actors, but he’d developed his own personal style during the execution.

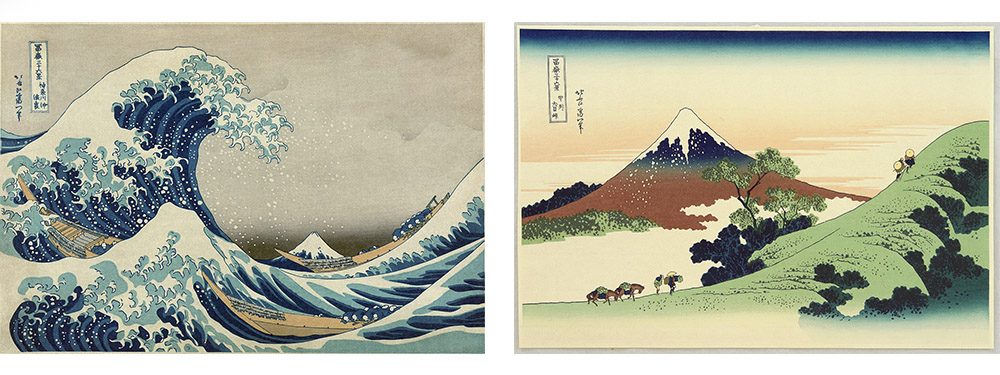

Artists have a tendency to paint what they know, and Hiroshige was no different. Because he grew up in Edo, he developed an extensive body of work focused on his home. Towards the beginning of his career, he had painted flora and fauna near modern-day Tokyo. He eventually evolved into more of a landscape painter – most likely due to his influence from Hokusai, the artist behind the incredibly popular series, “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.”

Hiroshige decided to fully pursue his career in the arts years later. He left his job as the fire warden to his brother, Tetsuzo, and decided to travel outside of Edo to paint new landscapes. His first wife was very supportive of his endeavors and sold her clothes and ornamental combs to help pay for his travels. During his that time, he painted the collections, “Illustrated Places of Naniwa,” “Famous Places of Kyoto,” and “Eight Views of Omi,” but he would always come back home to Edo.

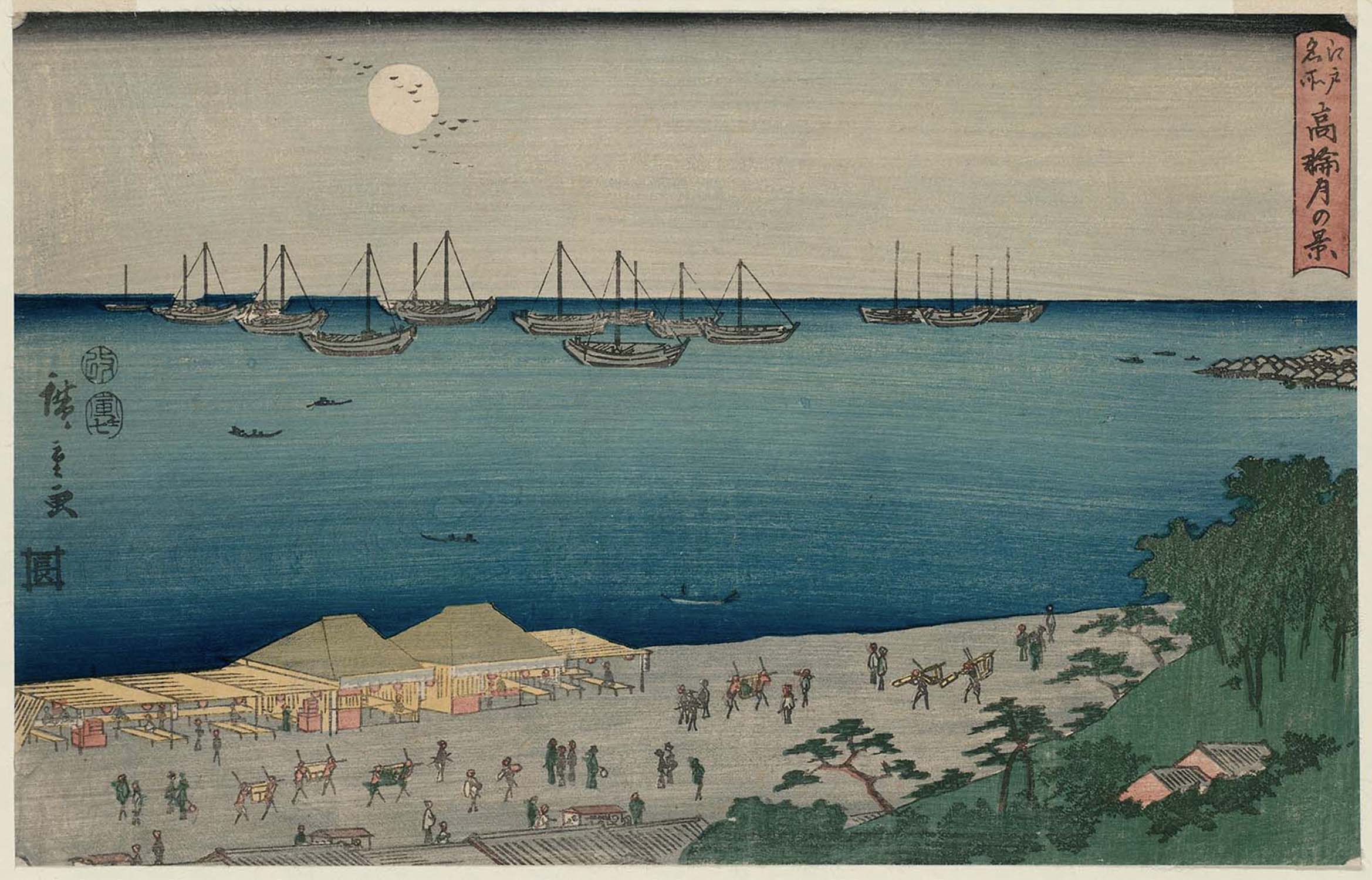

“View of Takanawa in Moonlight,” is a piece from Hiroshige’s series, “Famous Places in the Eastern Capital.” Here, Hiroshige designs a print of a familiar sight. “View of Takanawa in Moonlight,” is a view of present-day Tokyo Bay. This particular print is important because it depicts an early morning scene of the trading port. We know it’s early morning, rather than late at night because the sky is a hazy blue rather than a deep midnight color. Previous ukiyo-e prints depict nighttime with rich dark colors. In the bottom right portion of the composition, we see a Japanese marketplace, most likely specializing in fish due to its close proximity to the ocean. You see a number of fisherman sailing on their small boats in the water looking to get their early morning catch. Some people are carrying bountiful earnings from the boats to the market for preparation and distribution.

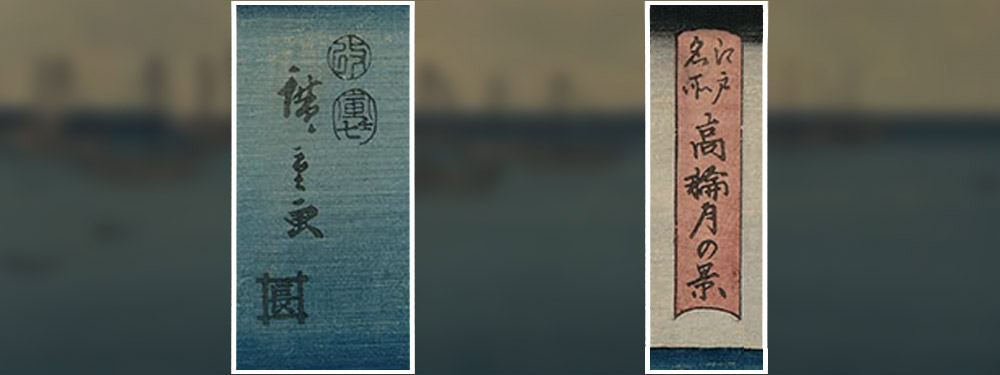

Hiroshige’s print has a few Japanese characters on it. The left side contains three different types of information. First, we see the artist’s signature. These are the three characters located on the leftmost side stacked on top of one another. To the right of them, there are two Kanji characters enclosed in circles. During the time the Tokugawas were in power, there was a strict system in place that determined what art was and wasn’t appropriate for the public. Everything needed a seal of approval before it could be released. This practice ended a few years after this print was approved. Underneath Hiroshige’s signature and the seals of approval, we see a Kanji character inside of a box. Though this character isn’t very common anymore, it signifies inner consideration and mindfulness. The ukiyo-e’s name is written in the red box to the right end of the print.

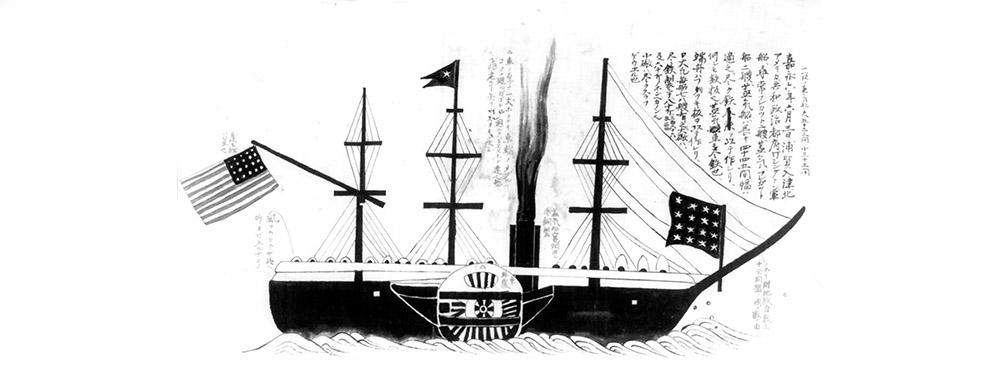

The most notable feature of Hiroshige’s composition is the larger boats on the horizon line. They’re much larger than the Japanese vessels used for fishing. Because the print was created in 1854, we know the ships in the horizon were most likely foreigner vessels. During the Edo period foreigners weren’t allowed to travel or trade with the Japanese. This was the case until 1853. Japan’s recent, though reluctant, choice to open their borders in certain ports, explains the European vessels in Tokyo Bay. Hiroshige’s work is mostly poetic and ambient, so it would make sense that he would portray this scene as an impartial observer. The foreign visitors don’t look threatening in any way, they just look as though they’re part of the quiet, early morning scene.

In 1600, Japan was unified under the Tokugawa Shogunate with emphasis on the reestablishment of order following one hundred years of civil war. It was the civil war that created the chaos that allowed the Tokugawas to take control in the first place, and their approach to governing Japan was militaristic, to say the least. Though they were incredibly strict, Japan did live in peace and stability during their rule. The military class was demilitarized – they kept all of their practices, except the warfare.

City people became more relevant, rather than the extreme polarization we had seen before where the leaders were rich, and the citizens lived in poverty. This new rule leads to the rise of the chonin, and a more comfortable middle class.

During the time, the Japanese became weary of Europeans spreading their ideas of Christianity to the Eastern nations. The Tokugawa Shogunate was suspicious of the Dominican and Franciscan missionaries that arrived in the Philippines looking to spread the word on Christianity only to dominate the country. Because of this, Tokugawa Ieyasu decided to end all Christian practice in Japan, as well as prohibit trade with western nations. This embargo was called the “Act of Seclusion” and was established in 1636. It remained active for the next 200 years until American Matthew Perry interrupted it.

In 1853, American Commodore Matthew Perry led his fleet of ships into Tokyo Bay, looking to re-establish regular trade between Japan and the western world since Japan ended relations with persistent Europeans looking to convert them to Catholicism. Since America started using California as a trade port, pursuing trade with China and Japan would be easier and beneficial for the western nation. Not only that, but Americans were finding themselves stranded in Japan due to ship malfunctions on their way to China. They were usually greeted with hostility, and America was hoping to work out a deal where Japan offers coaling stations to Americans on their way.

The deal seemed fair, but to ensure it went in favor of America, Commodore Perry brought an armed fleet to Japan when he tried to arrange a deal. To prove he knew little about the political situation in Japan, he asked to speak to the emperor rather than Tokugawa Ieyasu. Once he was directed properly, Japan reluctantly agreed to lift the “Act of Seclusion” on their own terms. They felt that if they were forced into the decision, it may end in war. Doing it on their own accord would be better in the long run. They wanted to ease into the trade, however. They agreed to open two American coaling stations where they allowed Americans to live and operate in peace, and they opened a few ports in Japan for global trade – just not all of them.

Japan opening their ports provided them with a lot of opportunities. Unfortunately, it also meant that the art of woodblock printing would also come to an end.

In 1858, Hiroshige passed away. This would go on to be known as the beginning of the end of ukiyo-e. Toward the end of his life, trade was re-established in Japan causing it to move into a progressive era. The country faced westernization due to the tools and knowledge they were adopted from the foreigners they once tried to seclude themselves from. Today, woodblock printing is appreciated as an ancient art form and is practiced as a nostalgic look at traditional Japanese culture, but it’s lost the weight it once held in their society. Looking back, Hiroshige was one of the great masters of ukiyo-e, and his contribution and unbiased observational eye will never be forgotten.